- John the Ripper is a password cracker that’s currently available on multiple platforms including Linux and Windows. Using the traditional Data Encryption Standard we see that the 2990WX and 7980XE.

- Several things for me to work on/look into. One of these is GPU support under Windows for John the Ripper's bleeding-jumbo version. I cloned the repository from GitHub and managed to compile under Windows with Cygwin. Then I procceeded to create a makefile rule called 'win32-cygwin-x86-opencl' where I tried to add the required flags for OpenCL.

- See Full List On Openwall.info

- GitHub - Openwall/john: John The Ripper Jumbo - Advanced ..

- John The Ripper Use Gpu

- John The Ripper Gpu Support Windows

John the Ripper is a fast password cracker, currently available for many flavors of Unix, Windows, DOS, and OpenVMS. Folder lock activator.

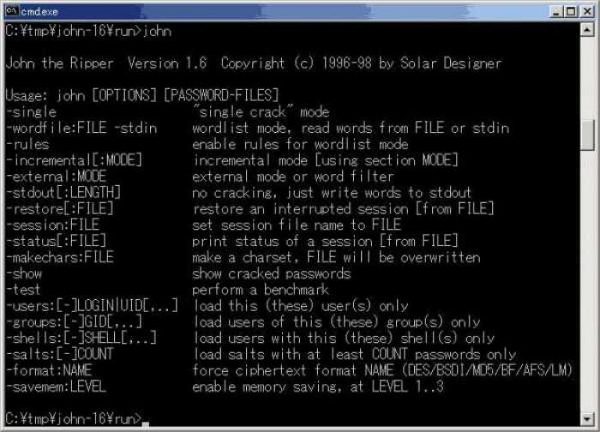

JOHN THE RIPPER:- John the ripper is a password cracker tool, which try to detect weak passwords. John the ripper can run on wide variety of passwords and hashes. This tool is also helpful in recovery of the password, in care you forget your password, mention ethical hacking professionals.

John the ripper is popular because of the dictionary attacks & is mainly is used in bruteforce attacks. Ethical hacking researcher of iicybersecurity said this method is useful because many old firms still uses the windows old versions which is not good in terms of cybersecurity.

CRACKING THE WINDOWS:-

In windows, password is typically stored in SAM file in %SystemRoot%system32config. Windows uses the NTLM hash. During the boot time the hashes from the SAM file gets decrypted using SYSKEY and hashes is loaded in registry which is then used for authentication purpose, according to ethical hacking courses.

Windows does not allow users to copy the SAM file in another location so you have to use another OS to mount windows over it and copy the SAM file. Once the file is copied we will decrypt the SAM file with SYSKEY and get the hashes for breaking the password.

In below case we are using Kali Linux OS to mount the windows partition over it.

- For making the bootable disk you can use rufus freeware which is available here: https://rufus.ie/en_IE.html

- This freeware is very easy to use. You simply have to select Kali linux iso image for making bootable disk.

- After creating the boot disk. Simply boot with bootable disk and follow steps as mentioned below:

- First you have to check the hard disk partition that where is the windows is installed. For that type fdisk -l.

CHECKING THE HARD DISK PARTITIONS:-

- In the above screen shot, after executing the query the command has shown 3 partitions of the target hard disk. By looking at size of partition you can know that where the target OS (Windows) in installed.

MOUNT:-

- Type mkdir /mnt/CDrive for creating the directory.

- For mounting the hard disk partition /dev/sda2 to CDrive directory,type mount /dev/sda2 /mnt/tmp/CDrive

- Then for checking the mount point. Type ls -ltr /mnt/tmp/CDrive

- Type mount to check the mounted drive

- In the above output, last line shows that target hard disk partition has been mounted to CDrive directory.

COPYING THE SAM FILE:-

- Type mkdir /tmp/temp

- Type cp /mnt/CDrive/Windows/System32/config/SAM /tmp/temp

SAM FILE:-

- Samdump2 fetches the SYSKEY and extract hashes from windows SAM file.

- For installing the samdump2 type sudo apt-get update after then type sudo apt-get install samdump2.

COPYING THE SYSTEM FILE:-

- Now copy the SYSKEY file, type cp /mnt/CDrive/Windows/System32/config/SYSTEM /tmp/temp

- Type samdump2 SYSTEM SAM

- In the above screen shot, after executing samdump2. The samdump2 will show the hashes in SAM files. In the next red marked there are 4 users on the target system.

- Now type samdump2 SYSTEM SAM > hash.txt for redirect the hash output to a file named hash.txt.

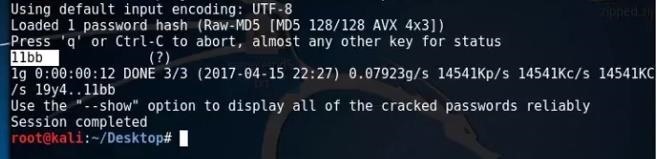

CRACKING PASSWORD USING JOHN THE RIPPER:-

- Type john –format=LM –wordlist=/root/usr/share/john/password_john.txt hash.txt

- In the above screen shot after executing above query. The wordlist will be used to crack the password. As shown above the current password for the target OS is 123456.

- Attacker can also use his own wordlist for cracking the password. In kali linux many wordlists are available that can be used in cracking. For using the kali linux wordlist go to -> /usr/share/wordlists/

NOTE:- The above method will work till WINDOWS 7 Operating system. It will not work on WINDOWS 8/8.1/10

In cryptanalysis and computer security, password cracking is the process of recovering passwords[1] from data that has been stored in or transmitted by a computer system in scrambled form. A common approach (brute-force attack) is to repeatedly try guesses for the password and to check them against an available cryptographic hash of the password.[2]

The purpose of password cracking might be to help a user recover a forgotten password (installing an entirely new password is less of a security risk, but it involves System Administration privileges), to gain unauthorized access to a system, or to act as a preventive measure whereby system administrators check for easily crackable passwords. On a file-by-file basis, password cracking is utilized to gain access to digital evidence to which a judge has allowed access, when a particular file's permissions are restricted.

Time needed for password searches[edit]

The time to crack a password is related to bit strength (seepassword strength), which is a measure of the password's entropy, and the details of how the password is stored. Most methods of password cracking require the computer to produce many candidate passwords, each of which is checked. One example is brute-force cracking, in which a computer tries every possible key or password until it succeeds. With multiple processors, this time can be optimized through searching from the last possible group of symbols and the beginning at the same time, with other processors being placed to search through a designated selection of possible passwords.[3] More common methods of password cracking, such as dictionary attacks, pattern checking, word list substitution, etc. attempt to reduce the number of trials required and will usually be attempted before brute force. Adobe edge animate crack. Higher password bit strength exponentially increases the number of candidate passwords that must be checked, on average, to recover the password and reduces the likelihood that the password will be found in any cracking dictionary.[4]

The ability to crack passwords using computer programs is also a function of the number of possible passwords per second which can be checked. If a hash of the target password is available to the attacker, this number can be in the billions or trillions per second, since an offline attack is possible. If not, the rate depends on whether the authentication software limits how often a password can be tried, either by time delays, CAPTCHAs, or forced lockouts after some number of failed attempts. Another situation where quick guessing is possible is when the password is used to form a cryptographic key. In such cases, an attacker can quickly check to see if a guessed password successfully decodes encrypted data.

For some kinds of password hash, ordinary desktop computers can test over a hundred million passwords per second using password cracking tools running on a general purpose CPU and billions of passwords per second using GPU-based password cracking tools[1][5][6] (See: John the Ripper benchmarks).[7] The rate of password guessing depends heavily on the cryptographic function used by the system to generate password hashes. A suitable password hashing function, such as bcrypt, is many orders of magnitude better than a naive function like simple MD5 or SHA. A user-selected eight-character password with numbers, mixed case, and symbols, with commonly selected passwords and other dictionary matches filtered out, reaches an estimated 30-bit strength, according to NIST. 230 is only one billion permutations[8] and would be cracked in seconds if the hashing function is naive. When ordinary desktop computers are combined in a cracking effort, as can be done with botnets, the capabilities of password cracking are considerably extended. In 2002, distributed.net successfully found a 64-bit RC5 key in four years, in an effort which included over 300,000 different computers at various times, and which generated an average of over 12 billion keys per second.[9]

Graphics processors can speed up password cracking by a factor of 50 to 100 over general purpose computers for specific hashing algorithms. As of 2011, available commercial products claim the ability to test up to 2,800,000,000 passwords a second on a standard desktop computer using a high-end graphics processor.[10] Such a device can crack a 10 letter single-case password in one day. The work can be distributed over many computers for an additional speedup proportional to the number of available computers with comparable GPUs.[citation needed]. However some algorithms are or even are specifically designed to run slow on GPUs. Examples include (triple) DES, bcrypt , scrypt and Argon2.

The emergence of hardware acceleration over the past decade GPU has enabled resources to be used to increase the efficiency and speed of a brute force attack for most hashing algorithms. In 2012, Stricture Consulting Group unveiled a 25-GPU cluster that achieved a brute force attack speed of 350 billion guesses per second, allowing them to check password combinations in 5.5 hours. Using ocl-Hashcat Plus on a Virtual OpenCL cluster platform[11], the Linux-based GPU cluster was used to 'crack 90 percent of the 6.5 million password hashes belonging to users of LinkedIn.'[12]

For some specific hashing algorithms, CPUs and GPUs are not a good match. Purpose made hardware is required to run at high speeds. Custom hardware can be made using FPGA or ASIC technology. Development for both technologies is complex and (very) expensive. In general, FPGAs are favorable in small quantities, ASICs are favorable in (very) large quantities, more energy efficient and faster. In 1998, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) built a dedicated password cracker using ASICs. Their machine, Deep Crack, broke a DES 56-bit key in 56 hours, testing over 90 billion keys per second[13]. In 2017, leaked documents show that ASICs are used for a military project to code-break the entire internet[14]. Designing and buildig ASIC-basic password crackers is assumed to be out of reach for non-governments. Since 2019, John the Ripper supports password cracking for a limited number of hashing algorithms using FPGAs[15]. FPGA-based setups are now in use by commercial companies for password cracking[16].

Easy to remember, hard to guess[edit]

Passwords that are difficult to remember will reduce the security of a system because (a) users might need to write down or electronically store the password using an insecure method, (b) users will need frequent password resets and (c) users are more likely to re-use the same password. Similarly, the more stringent requirements for password strength, e.g. 'have a mix of uppercase and lowercase letters and digits' or 'change it monthly', the greater the degree to which users will subvert the system.[17]

In 'The Memorability and Security of Passwords',[18] Jeff Yan et al. examines the effect of advice given to users about a good choice of password. They found that passwords based on thinking of a phrase and taking the first letter of each word are just as memorable as naively selected passwords, and just as hard to crack as randomly generated passwords. Combining two unrelated words is another good method. Having a personally designed 'algorithm' for generating obscure passwords is another good method.

However, asking users to remember a password consisting of a 'mix of uppercase and lowercase characters' is similar to asking them to remember a sequence of bits: hard to remember, and only a little bit harder to crack (e.g. only 128 times harder to crack for 7-letter passwords, less if the user simply capitalizes one of the letters). Asking users to use 'both letters and digits' will often lead to easy-to-guess substitutions such as 'E' → '3' and 'I' → '1', substitutions which are well known to attackers. Similarly typing the password one keyboard row higher is a common trick known to attackers.

Research detailed in an April 2015 paper by several professors at Carnegie Mellon University shows that people's choices of password structure often follow several known patterns. As a result, passwords may be much more easily cracked than their mathematical probabilities would otherwise indicate. Passwords containing one digit, for example, disproportionately include it at the end of the password.[19]

See Full List On Openwall.info

Incidents[edit]

On July 16, 1998, CERT reported an incident where an attacker had found 186,126 encrypted passwords. By the time they were discovered, they had already cracked 47,642 passwords.[20]

In December 2009, a major password breach of the Rockyou.com website occurred that led to the release of 32 million passwords. The attacker then leaked the full list of the 32 million passwords (with no other identifiable information) to the internet. Passwords were stored in cleartext in the database and were extracted through a SQL Injection vulnerability. The Imperva Application Defense Center (ADC) did an analysis on the strength of the passwords.[21]

In June 2011, NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) experienced a security breach that led to the public release of first and last names, usernames, and passwords for more than 11,000 registered users of their e-bookshop. The data were leaked as part of Operation AntiSec, a movement that includes Anonymous, LulzSec, as well as other hacking groups and individuals.[22]

On July 11, 2011, Booz Allen Hamilton, a large American Consulting firm that does a substantial amount of work for the Pentagon, had their servers hacked by Anonymous and leaked the same day. 'The leak, dubbed 'Military Meltdown Monday,' includes 90,000 logins of military personnel—including personnel from USCENTCOM, SOCOM, the Marine Corps, various Air Force facilities, Homeland Security, State Department staff, and what looks like private sector contractors.'[23] These leaked passwords wound up being hashed with unsaltedSHA-1, and were later analyzed by the ADC team at Imperva, revealing that even some military personnel used passwords as weak as '1234'.[24]

On July 18, 2011, Microsoft Hotmail banned the password: '123456'.[25]

How to Open a Port in Ubuntu Firewall. In This UFW Tutorial We are going to Learn How to open a port in Ubuntu Firewall. Ufw allow command use to open port in Ubuntu Firewall.By default, if you did not specify the protocol, the port will open for both TCP and UDP protocols. Is it using any of these ports for program data transfer? Seems strange to me. Or is there an overriding exception pre-defined in Ubuntu (this is a new setup, 12.04)? What is probably the case here, and what port does the Software Center use for program data (I assume it does use HTTP for the interface and list entries, but the programs. Ubuntu.com; Ubuntu Wiki. Search: Immutable Page; Info; Attachments; More Actions: Ubuntu Wiki; Login; Help; Ports. While most Ubuntu users are using so called x86/x86-64 hardware, Ubuntu also targets other architectures, such as PowerPC, or ARM. How does development differ on these architectures? It's mostly the same, except slower and with. Ubuntu connect com port. Network port is identified by its number, the associated IP address, and the type of the communication protocol such as TCP or UDP. To identify listening ports on Ubuntu follow the steps below: Use the netstat Command.

In July 2015, a group calling itself 'The Impact Team' stole the user data of Ashley Madison. Many passwords were hashed using both the relatively strong bcrypt algorithm and the weaker MD5 hash. Attacking the latter algorithm allowed some 11 million plaintext passwords to be recovered.

Prevention[edit]

One method of preventing a password from being cracked is to ensure that attackers cannot get access even to the hashed password. For example, on the Unixoperating system, hashed passwords were originally stored in a publicly accessible file /etc/passwd. On modern Unix (and similar) systems, on the other hand, they are stored in the shadow password file /etc/shadow, which is accessible only to programs running with enhanced privileges (i.e., 'system' privileges). This makes it harder for a malicious user to obtain the hashed passwords in the first instance, however many collections of password hashes have been stolen despite such protection. And some common network protocols transmit passwords in cleartext or use weak challenge/response schemes.[26][27]

Another approach is to combine a site-specific secret key with the password hash, which prevents plaintext password recovery even if the hashed values are purloined. However privilege escalation attacks that can steal protected hash files may also expose the site secret. A third approach is to use key derivation functions that reduce the rate at which passwords can be guessed.[28]:5.1.1.2

Another protection measure is the use of salt, a random value unique to each password that is incorporated in the hashing. Salt prevents multiple hashes from being attacked simultaneously and also prevents the creation of precomputed dictionaries such as rainbow tables.

Modern Unix Systems have replaced the traditional DES-based password hashing function crypt() with stronger methods such as crypt-SHA, bcrypt and scrypt.[29] Other systems have also begun to adopt these methods. For instance, the Cisco IOS originally used a reversible Vigenère cipher to encrypt passwords, but now uses md5-crypt with a 24-bit salt when the 'enable secret' command is used.[30] These newer methods use large salt values which prevent attackers from efficiently mounting offline attacks against multiple user accounts simultaneously. The algorithms are also much slower to execute which drastically increases the time required to mount a successful offline attack.[31]

Many hashes used for storing passwords, such as MD5 and the SHA family, are designed for fast computation with low memory requirements and efficient implementation in hardware. Multiple instances of these algorithms can be run in parallel on graphics processing units (GPUs), speeding cracking. As a result, fast hashes are ineffective in preventing password cracking, even with salt. Some key stretching algorithms, such as PBKDF2 and crypt-SHA iteratively calculate password hashes and can significantly reduce the rate at which passwords can be tested, if the iteration count is high enough. Other algorithms, such as scrypt are memory-hard, meaning they require relatively large amounts of memory in addition to time-consuming computation and are thus more difficult to crack using GPUs and custom integrated circuits.

In 2013 a long-term Password Hashing Competition was announced to choose a new, standard algorithm for password hashing[32], with Argon2 chosen as the winner in 2015.Another algorithm, Balloon, is recommended by NIST.[33] Both algorithms are memory-hard.

Solutions like a security token give a formal proof answer by constantly shifting password. Those solutions abruptly reduce the timeframe available for brute forcing (attacker needs to break and use the password within a single shift) and they reduce the value of the stolen passwords because of its short time validity.

Software[edit]

There are many password cracking software tools, but the most popular[34] are Aircrack, Cain and Abel, John the Ripper, Hashcat, Hydra, DaveGrohl and ElcomSoft. Many litigation support software packages also include password cracking functionality. Most of these packages employ a mixture of cracking strategies, algorithm with brute force and dictionary attacks proving to be the most productive.[35]

The increased availability of computing power and beginner friendly automated password cracking software for a number of protection schemes has allowed the activity to be taken up by script kiddies.[36]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ aboclHashcat-lite – advanced password recovery. Hashcat.net. Retrieved on January 31, 2013.

- ^Montoro, Massimiliano (2009). 'Brute-Force Password Cracker'. Oxid.it. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2013.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- ^Bahadursingh, Roman (January 19, 2020). [Roman Bahadursingh. (2020). A Distributed Algorithm for Brute Force Password Cracking on n Processors. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3612276 'A Distributed Algorithm for Brute Force Password Cracking on n Processors'] Check

|url=value (help). zenodo.org. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3612276. - ^Lundin, Leigh (August 11, 2013). 'PINs and Passwords, Part 2'. Passwords. Orlando: SleuthSayers.

- ^Alexander, Steven. (June 20, 2012) The Bug Charmer: How long should passwords be?. Bugcharmer.blogspot.com. Retrieved on January 31, 2013.

- ^Cryptohaze Blog: 154 Billion NTLM/sec on 10 hashes. Blog.cryptohaze.com (July 15, 2012). Retrieved on 2013-01-31.

- ^John the Ripper benchmarks. openwall.info (March 30, 2010). Retrieved on 2013-01-31.

- ^Burr, W. E.; Dodson, D. F.; Polk, W. T. (2006). 'Electronic Authentication Guideline'(PDF). NIST. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-63v1.0.2. Retrieved March 27, 2008.Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^'64-bit key project status'. Distributed.net. Archived from the original on September 10, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^Password Recovery Speed table, from ElcomSoft. NTLM passwords, Nvidia Tesla S1070 GPU, accessed February 1, 2011

- ^http://www.mosix.org/txt_vcl.html/

- ^'25-GPU cluster cracks every standard Windows password in <6 hours'. 2012.

- ^'EFF DES Cracker machine brings honesty to crypto debate'. EFF. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^'NYU ACCIDENTALLY EXPOSED MILITARY CODE-BREAKING COMPUTER PROJECT TO ENTIRE INTERNET'.

- ^'John the Ripper 1.9.0-jumbo-1'.

- ^'Bcrypt password cracking extremely slow? Not if you are using hundreds of FPGAs!'.

- ^Managing Network Security. Fred Cohen & Associates. All.net. Retrieved on January 31, 2013.

- ^Yan, J.; Blackwell, A.; Anderson, R.; Grant, A. (2004). 'Password Memorability and Security: Empirical Results'(PDF). IEEE Security & Privacy Magazine. 2 (5): 25. doi:10.1109/MSP.2004.81. S2CID206485325.

- ^Steinberg, Joseph (April 21, 2015). 'New Technology Cracks 'Strong' Passwords – What You Need To Know'. Forbes.

- ^'CERT IN-98.03'. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^'Consumer Password Worst Practices'(PDF).

- ^'NATO Hack Attack'. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^'Anonymous Leaks 90,000 Military Email Accounts in Latest Antisec Attack'. July 11, 2011.

- ^'Military Password Analysis'. July 12, 2011.

- ^'Microsoft's Hotmail Bans 123456'. Imperva. July 18, 2011. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012.

- ^Singer, Abe (November 2001). 'No Plaintext Passwords'(PDF). Login. 26 (7): 83–91. Archived from the original(PDF) on September 24, 2006.

- ^Cryptanalysis of Microsoft's Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol. Schneier.com (July 7, 2011). Retrieved on 2013-01-31.

- ^Grassi, Paul A (June 2017). 'SP 800-63B-3 – Digital Identity Guidelines, Authentication and Lifecycle Management'. NIST. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-63b.Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^A Future-Adaptable Password Scheme. Usenix.org (March 13, 2002). Retrieved on 2013-01-31.

- ^MDCrack FAQ 1.8. None. Retrieved on January 31, 2013.

- ^Password Protection for Modern Operating Systems. Usenix.org. Retrieved on January 31, 2013.

- ^'Password Hashing Competition'. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^NIST SP800-63B Section 5.1.1.2

- ^'Top 10 Password Crackers'. Sectools. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^'Stay Secure: See How Password Crackers Work - Keeper Blog'. Keeper Security Blog - Cybersecurity News & Product Updates. September 28, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^Anderson, Nate (March 24, 2013). 'How I became a password cracker: Cracking passwords is officially a 'script kiddie' activity now'. Ars Technica. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

External links[edit]

GitHub - Openwall/john: John The Ripper Jumbo - Advanced ..

- Philippe Oechslin: Making a Faster Cryptanalytic Time-Memory Trade-Off. CRYPTO 2003: pp617–630

John The Ripper Use Gpu

John The Ripper Gpu Support Windows